A complex crime

Published 5:38 pm Friday, August 23, 2019

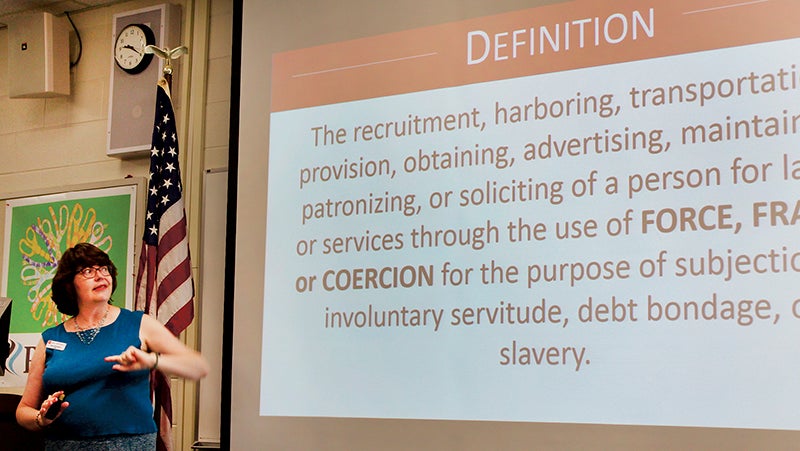

- Pam Strickland, founder of NC Stop Human Trafficking, explains the definition of human trafficking at the outset of Wednesday’s training seminar held at Roanoke-Chowan Community College. Staff Photo by Holly Taylor

Part 1 of a 3-part series

AHOSKIE – The phrase “human trafficking” often evokes a terrifying image of a young person being forcefully kidnapped by a stranger and then smuggled far away, never to be seen again. Reality, however, is usually a lot different and often more complex than Hollywood portrayals of the crime.

Roanoke-Chowan S.A.F.E., a local nonprofit which provides services to abuse victims, recently partnered with UNC-Greensboro, S.A.F.E. of Rocky Mount, and NC Stop Human Trafficking for a training session on Wednesday, Aug. 21 open to law enforcement, prosecutors, and victims service providers. Attendees from Hertford, Bertie, Northampton, and Gates counties gathered at the Roanoke-Chowan Community College campus to learn more about the issue.

“We have this idea in our head that’s been planted there by Hollywood that kidnapping is the big way [it happens], and it terrifies us as parents and grandparents. But really what we need to be more concerned about is who they’re hanging out with,” explained Pam Strickland, founder of the organization NC Stop Human Trafficking.

Strickland hosted the first presentation of the day to explain in detail what human trafficking really is and what red flags to look for.

North Carolina is ranked tenth in the nation for human trafficking with 287 cases in 2018. But Strickland explained that rank is based on cases from calls into the national Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888). Cases are sometimes reported to law enforcement entities or service providers, so the actual numbers may be even higher.

“The call that you get is rarely going to be ‘I have a human trafficking victim here.’ It might be a domestic violence situation, an assault, a robbery, a rape,” Strickland emphasized. “We have to keep our eyes open and look at everything and figure out what’s actually going on.”

The basic definition of human trafficking is when people are forced, defrauded, or coerced into carrying out labor or sexual services against their will.

“Anybody who was involved at any point during the person’s victimization can be charged with the crime of human trafficking,” she said, noting that can entail things like recruiting, transporting, advertising, and patronizing the victim.

In the United States, it’s rare for someone to be forced into a human trafficking situation by kidnapping. More commonly, Strickland explained, the victim is coerced into the situation by someone they know such as a friend, intimate partner, or even family members.

A common situation is what Strickland called “relationship fraud” where someone acts like a trusted friend or boyfriend and then begins to make demands from the victim, such as performing sexual services to earn money. “Opportunity fraud” often occurs when victims, usually from outside the United States, are promised a job opportunity and a good life if they travel with the trafficker. When they arrive, however, they’re forced into work against their will.

Victims can be subject to confinement, beatings, rape, manipulation and mind games, threats of violence against their children, and more in order to force them into labor or sexual services.

Strickland shared examples of several different cases in North Carolina to show the different ways human trafficking crimes can take shape.

A Wilson County man, for example, began “dating” a 13-year-old girl. He then repeatedly sold her to migrant camps for sexual services. The man gained control over the victim by getting her addicted to drugs.

Another example was a Cumberland County minister who required his parishioners to live in a compound and work at businesses he owned. His crimes were eventually uncovered because he had forced minors to work at a fish market.

A woman in Wake County worked as a pimp to recruit young girls until she was caught. Strickland noted that the woman didn’t fit the stereotypical look people imagine.

“There’s no set profile of what a trafficker looks like,” she said.

Closer to home in Pitt County, a teenage girl was caught passing counterfeit money at a store. After more investigation by law enforcement, it was discovered that the girl was a runaway from New York and was being held in a nearby hotel. The trafficker preyed on her vulnerabilities stemming from her desire to run away.

“It can happen in a lot of different ways. It doesn’t happen like it happens in the movies,” Strickland reminded everyone.

She outlined the kinds of people who are typically most vulnerable to human trafficking. Those groups can include runaways, homeless youth, LGBTQ youth, people with substance abuse problems, women associated with gangs, childhood sexual abuse victims, people with mental illness or developmental delays, and people with a general lack of social support.

“Traffickers will very often use a substance as a way of gaining control over their victims,” she said, explaining how that often complicates the crime.

According to Strickland, there are plenty of other red flags that may indicate a human trafficking crime is happening.

Victims often have their IDs, like passports and drivers license, taken away by the trafficker. Victims may also not be in control of their own money. They may also begin traveling a lot more than before even if it seems like they cannot afford it. Other red flags can include increased promiscuity, or increased anxiety and depression.

Places with unusual security measures, such as a trailer with lots of security cameras, can also be an indicator that something illegal is happening inside. An abandoned building suddenly frequented by many people might be a place where human trafficking is happening. A business where employees all arrive together or live in the place of business may also indicate a trafficking situation.

“These are red flags for a lot of different things, not just human trafficking,” Strickland acknowledged. “What you need to do is look at the whole context of the situation, and most importantly, you need to do a gut check.”

Strickland encouraged the training attendees to be aware of potential human trafficking situations because they often look different than expected.

Next in the series: how to understand and deal with victim trauma