‘Misplaced’ Colony

Published 8:49 am Thursday, June 4, 2015

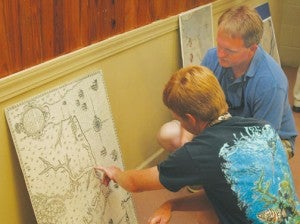

Brent Lane (right) and a group of First Colony Foundation archeologists address a large audience at the Windsor Community on the theory the Lost Colony relocated to Bertie County in 1587. In the foreground are artifacts excavated near Merry Hill. Staff Photo by Gene Motley

WINDSOR – Brent Lane, a Board of Directors member of the First Colony Foundation, will quickly tell you there were plenty of ‘lost’ colonies in the New World back in the 16th century.

However, he will just as swiftly add that there is really only one ‘Lost Colony’.

Lane, whose primary job is Director of the UNC Center for Competitive Economies at the Kenan Flagler Business School for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is one of the researchers leading the charge to find out additional information about the possibility of the Lost Colony’s relocation to Bertie County along the western bank of the Albemarle Sound. That was exactly what he, along with a group of his fellow archeologists from First Colony Foundation (FCF), spoke about before a group gathered at the Windsor Community Building on Saturday.

Archeologist Bly Straube displays some of the pottery artifacts from the excavation at the probable Roanoke colony’s Bertie County site near Salmon Creek. Staff Photo by Gene Motley

“What we have today is a chance to talk with the folks in the Bertie County community about something that’s an important part of their own heritage that’s been recently been discovered by archeologists and historians,” Lane said. “What’s been discovered is that some part of the Lost Colony, when they left Roanoke Island (in Dare County), came to Bertie County. We don’t yet know how many, and we don’t know for how long, but the evidence we have now is that a small group of “lost colonists” who, when they stated their purpose was to move from Roanoke Island 50 miles into the mainland, some of them came to Bertie County.”

For those whose history is a bit rusty, or who never may have known, in the late 16th century Sir Walter Raleigh, a wealthy English courtier and favorite of Queen Elizabeth I, sponsored expeditions to settle the Outer Banks and Chesapeake regions of the eastern U.S.

Captains of an early scouting trip in 1584 had identified Roanoke Island – off North Carolina’s coast – as a suitable place for the first English colony; and in 1585-86 Raleigh sent 108 men to explore the area. In 1587 the “Citte of Raleigh” was established with more than 100 settlers – men, women, and children – living on the island.

But three years later when a British ship returned to the island to drop off supplies, the settlers were nowhere to be found. All that was left of the settlers on the island was a carving on a tree reading “CROATOAN,” which likely referred to the Croatoan Island 50 miles south in what is modern-day Hatteras.

“There are four main theories of what happened to the settlers,” Lane explains. “One, that they met their deaths by disease, starvation, or attacks from either the Indians or the Spaniards who had some up from Florida to wipe out the English colonists; and a second option is that the group, in some part, relocated north to the harbors of Chesapeake Bay Virginia where they thought that was a better place for their ships than the Outer Banks.”

Lane says the third theory was that part of the settlers merged with the Lumbee Indians who inhabited the northeastern region of North Carolina before their migration to what is now Robeson County.

And the fourth theory, which marked a great portion of his lecture, was a re-settlement on the Albemarle Sound in modern-day Bertie County.

Raleigh’s early explorers were known for their detailed maps; and one of the more well known was the “Virginia Pars” map of eastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia, drawn by John White. That map has been preserved in the British Museum in London since 1866. In 2011, Lane noticed two paper “patches” where it appears the map had been corrected and made of paper contemporaneous with that of the map. Lane’s inquiry sparked a research investigation of not one, but two apparent patches on one map. Researchers at the museum especially closely examined the surface of the patch in Bertie County, and used modern scanning technology to look beneath the patch in 2012.

Jordan Rose (left) of Windsor points to an area indicated now as Bertie County on one of the 16th century maps used by New World explorers as Jody Sary of Merry Hill looks on. Staff Photo by Gene Motley

Researchers found a bright red and blue symbol of what appears to be a fort underneath the patch; and on the surface, they found a separate fort symbol in scratch marks, which are thought to be from the quill of a pen writing in invisible ink.

Sources made available after the colonists disappeared from Roanoke reference plans to resettle the mainland, and the fort in Bertie County is now suspected to be the realization of those plans.

“We already knew some of that from historic sources, including some of the reports from the Jamestown (VA) colony themselves from 400 years ago,” said Lane. “There were reports from the Indians in the area that there were survivors of Sir Walter Raleigh’s Roanoke colony living in the Chowan River area. What we have found through archeology is really to confirm what has already been reported by the Native Americans in the area: that the survivors of the Roanoke colony had in many ways become members of the Indian tribe, and had become members of the local Indian community themselves.”

Some scholars speculate the area where the colonists relocated is on what is now Salmon Creek, near Avoca Farms, in Merry Hill. The Scotch Hall Preserve golf course community had home sites planned on that site, but it has not fully developed the area in question.

In addition to Lane, Nick Luccketti, an FCF research archeologist, and Bly Straube – who works with Luccketti through the James River Institute in Williamsburg, VA – and Clay Swindell of the Museum of the Albemarle in Elizabeth City, spoke to the audience on some of the artifacts unearthed during the archeological digs. Among Straube’s findings were pottery of the period; perhaps adding to the mystery of the settlers’ whereabouts.

“Pottery was used for food preparation, storage, and serving,” Straube said. “It was not traded with the Indians in the New World because ceramic vessels were not favored by the Indians.”

Swindell reminded the audience that the south side of Salmon Creek (Scotch Hall) was part of the estate of Nathaniel Batts, a 16th century fur trader believed to be one of the first Europeans to permanently settle in North Carolina after migrating from Virginia around 1655.

Lane says it’s the cooperation of the 21st century landowners that’s essential to this project’s success.

“Unlike what many people think of government-led efforts, this is a not-for-profit foundation supported by citizens and access to land is essential. It’s through their cooperation that we can continue,” Lane said.

Billy Smithwick, Tourism Director for the town of Windsor, who sponsored Lane and his lecture, said the new evidence of the Lost Colony findings in Bertie County are a potential windfall.

“It can be a real large economic engine if it’s handled correctly,” Smithwick contended. “Windsor may not get a whole lot as much as the county as a whole would. I envision a Welcome Center that can draw people in to look at this sort of stuff because a lot of people are interested in the subject. Look at what happened with ‘The Lost Colony’ play out on the coast and how that’s grown.”

Lane hopes the excavation along the western shoreline of the Chowan River will continue.

“I think the current site needs to be expanded somewhat so we can learn more about that particular part of the Roanoke colony’s story here in Bertie County,” he observed. “But there are other areas in the northeastern part of North Carolina that have a part of this story as well. We’re continuing to work both on Roanoke Island where the story begins and also here in Bertie County where the story continues. We don’t know what direction the evidence will lead and that’s what’s fascinating. We just hope Bertie residents will want to share in this process.”