CSI – Ahoskie

Published 10:11 pm Friday, June 3, 2011

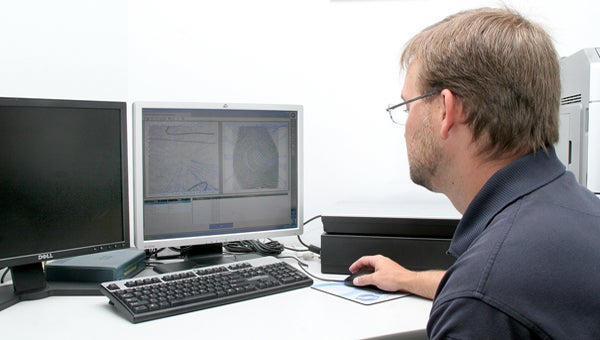

Ahoskie Police Detective Lt. Jeremy Roberts uses AFIS technology to study fingerprints from a recent criminal case he was able to solve. Staff Photo by Cal Bryant

AHOSKIE – The Town of Ahoskie bills itself as “The Only One.”

However, the town is unique in more ways than its one-of-a-kind name.

Tearing a page from the script of the numerous CSI (Crime Scene Investigation) shows that are all the rage on television, Ahoskie stands alone as the state’s only small town that boasts of a police department armed with hi-tech gadgetry normally reserved for cities/counties with bigger budgets and more law enforcement manpower.

The Ahoskie Police Department is home to AFIS (Automated Fingerprint Identification System). This crime-fighting tool can trim months of work off a criminal case, often leading to quicker arrests, which, in turn, offers a buffer of protection for potential victims.

Lt. Jeremy Roberts, a 14-year law enforcement veteran and the APD’s lead investigator, is the officer trained to operate AFIS. After months and months of training, Lt. Roberts is a certified Crime Scene Investigator and Fingerprint Expert.

“Lt. Roberts is part of 19 agencies here in North Carolina, including the SBI, as well as the FBI that are all connected by this system,” said Ahoskie Police Chief Troy Fitzhugh. “This is a great asset to not only the Ahoskie Police Department, but to the local area and the entire state as well. Our town has invested a lot in this system, money I feel is well spent when it comes to solving crime and protecting our citizens. I thank the mayor, town manager and town council for taking a proactive stance in the fight against crime.

“We don’t work for the FBI, we work with the FBI,” Fitzhugh added.

To witness the system in action is like watching one of the numerous CSI shows on TV.

“Yes, I guess you could relate this system to what you see on TV because the technology they use is the same in our line of work. The only difference is that we can’t bring this all together in one hour like you see on TV,” Roberts stressed.

Roberts said permission was gained from the FBI and SBI for the Ahoskie PD to purchase the equipment and become a part of their networks. That permission was necessary due to the fact that all the material sent and received at the AFIS workstation located in Roberts’ office is encrypted to prevent hackers from gaining access to the database.

Cards to computers

From the time that state and federal law enforcement agencies began taking fingerprints back in the 1930’s, millions upon millions of such ink impressions have been recorded. Prior to the onset of computer technology, all those fingerprint cards were stored away in filing cabinets at law enforcement agencies throughout the United States. Roberts said the FBI alone had a four-to-five story building full of such cabinets storing fingerprint cards.

Now with the AFIS technology, all those fingerprint cards have been transformed into digital images and downloaded into a national database.

“Anytime anyone has been arrested, it’s required that they are to be fingerprinted,” Roberts said. “Additionally, some businesses and other organizations require their employees to be fingerprinted. All those files, now all digital, are part of a national database, whether you are a criminal or not.”

All fingerprint images include personal information of the person – name, address, sex, height, weight and, if applicable, where the arrest, and on what charges, was made that generated this particular set of prints. If that person was transferred to the NC Department of Corrections, Roberts can enter that name into the DOC database for additional information concerning incarceration and probation/parole as well as whether or not the person has a DNA sample on file. All of that information can be obtained within a matter of minutes.

The AFIS technology also includes a printer that Roberts can use to print hard copies of the fingerprint cards. He can also instruct the system to print a card to any of the AFIS locations statewide.

Print ‘maps’

Before launching a search on the national database, Roberts initially “maps out” the fingerprint, which help narrow the search. That, in turn, gives him a quicker response from the database, some replies as fast as 10 minutes.

Using what he referred to as minuta points – ending ridges, enclosures and barification, all unique characteristics within an individual fingerprint – Roberts begins the effort to narrow the search. He first has to transfer the fingerprint, one lifted on tape from a crime scene by either himself or another officer, to a computer by using a high resolution camera (100,000 megapixel). He can place most any type of object under the camera to record a digital image of a fingerprint. There is an accompanying high resolution scanner that can transfer a fingerprint image from a card.

In one Ahoskie case, there were forged checks being cashed at a local bank. Roberts soaked the check in a chemical to raise the fingerprints, transferring it to his computer. He performed his minuta points check on the image; he can map out as many as 75-to-100 points (the database system only requires him to find seven).

“The more points I can map out, the faster and more precise the search will be,” Roberts noted.

He can expand that database search by asking for the top 10 or top 100, etc. possible matches.

“Once I receive those results, and this is where my training comes in, I have to make sure the computer is right; I have to verify it visually, even though the database search is telling me the number one match is 5,290 percent sure,” Roberts explained.

To show the detail involved between his observation of the top-ranked “hit” returned from the national database, Roberts mapped out the fingerprint using a computer program, revealing 48 points that were exactly the same.

The old-fashioned way of matching a fingerprint prior to AFIS was for a law enforcement agency to mail a fingerprint card to the SBI lab in Raleigh. Depending upon their case load, it may take the SBI six months to a year to respond.

“With AFIS, I can have an answer for those requesting our help within a couple of days, no more than one week,” Roberts said. “That helps out a lot if there is a rash of crime occurring. Say there’s a rash of break-ins that are occurring in several local jurisdictions. If there’s a fingerprint lifted at one scene, we can quickly find a match if that person is in the national database. That, in turn, leads to an arrest, thus preventing other possible criminal activity by this person.”

AFIS also allows Roberts to enlarge the fingerprints onto poster size boards, complete with color-coded arrows identifying the tell-tale minuta points, for use in court if he is asked to provide expert testimony.

Roberts’ training as a fingerprint expert is also witnessed outside his office. He is a certified Crime Scene Investigator for both the APD and Judicial District 6B (Bertie, Hertford and Northampton counties).

“Those local agencies do not have to contact the SBI to send a fingerprint expert to a crime scene,” Roberts said, adding that the closest SBI agent that could respond resides in Greenville. “I have the same training; have attended the same schools. I’m a lot closer and can be on a scene quicker. This system has helped us and others solve cases much quicker.”

Practice makes perfect

Roberts has been certified as a fingerprint expert for the last two years. It was only recently that the APD invested in AFIS. Prior to that technology, he read fingerprint cards with magnifying glasses or comparing the prints side-by-side on a computer screen.

Three years ago, Lt. Roberts launched his effort to become a fingerprint expert. He went through Basic and Advanced Fingerprint Examiner’s School, Crime Scene Processing School (how to use chemicals and other means to lift a fingerprint) and Palm Print School. All schools, conducted by a private company specializing in crime scene investigation equipment, were held in Youngsville, located near Wake Forest.

There are tests at each level of training, examinations that must be completed at a passing rate prior to becoming certified. To maintain his certification, Roberts is required to take annual remedial classes.

Having this extra responsibility, in addition to his regular duties as APD’s lead investigator, is no sweat for Roberts.

“It’s satisfying as a law enforcement officer to see all the work you put into a case lead to an arrest and eventual conviction,” Roberts concluded. “I feel very fortunate as a police officer that our town realized the need for such technology to help us, and other law enforcement agencies, solve crimes. I don’t know of another town of our size that has invested in this. It’s also not a problem on our department for me to be gone for any length of time to attend classes to gain this training or the time I have to invest in helping other law enforcement agencies. We have to wear a lot of hats here, but I feel that makes us a better police department.”

The total cost of the gadgets inside Roberts’ office came with an $83,000 price tag. The state covered $18,000 of those costs, providing that the Ahoskie Police Department would offer its AFIS capabilities to nearby law enforcement agencies. To date, the APD has assisted the Northampton County Sheriffs Office and police departments in Murfreesboro and Windsor in solving criminal cases.